Introduction¶

Overview¶

Reaction-diffusion systems can be used to model a large variety of complex self-organized phenomena occurring in biological, chemical, and social systems. The common macroscopic description of these systems, based on a Fokker-Planck equation (FPE), suffers from major limitations. Most importantly, it fails at low particle densities and it is impossible to incorporate individual-level experimental observations. A microscopic Langevin-type individual-based description can – in principle – address these issues but is challenging and computationally expensive to the point that hardware limitations severely restrict their applicability to models of realistic size. Inchman is a graphics-processor-accelerated stochastic simulation solver that obtains performance gains of up to two orders of magnitude even on workstations. We provide a versatile web-based editor allowing researcher to perform complex experiments and parameter studies. Inchman allows users to upload models of chemical reaction networks written in SBML, the lingua franca of systems biology, amend them with spatial information and run large-scale simulations.

Inchman provides an implementation of a spatially-resolved stochastic simulation algorithm on general-purpose graphics processing units (GPUs). This algorithm, designed to solve reaction-drift-diffusion equations on a mesoscopic level, has widespread applications in computational biology, molecular chemistry and social systems research. For our implementation, we use the Gillespie multi-particle method, which is well-suited for GPUs. Using this algorithm, we could obtain speed ups of several orders of magnitudes as compared to standard implementations on CPUs.

Reaction-Drift-Diffusion Systems¶

Reaction-drift-diffusion networks are systems consisting of one or more interacting entities (e.g. molecules in a solution) which propagate in space through (possibly biased) random walks. In many applications, most notably in a biological and chemical context, the number of participating agents is small and the inherently stochastic nature of the problem requires a microscopic description of the system, in which the position of every species is known at all times. On a microscopic level, the spatial movement of individuals can be described by an Ito stochastic-differential equation (SDE):

where \(\mathbf{X}_t\) is a stochastic process denoting the position of an individual in space. \(\mathbf{W}_t\) is a multi-variable Wiener process. Statistical averaging of Eq. (1) yields the corresponding Fokker-Planck-Equation (FPE), which has the form of a classical drift-diffusion equation

Gillespie-Multiparticle Algorithm¶

A wide variety of stochastic simulation algorithms exist to compute single realizations of reaction diffusion networks (see, e.g., [Vigelius2010], [Vigelius2012a] for a brief overview). Gillespie’s direct method [Gillespie2007] has emerged as a standard method to simulate spatially homogeneous reaction networks. Very efficient adaptations of this algorithm exist, such as the next-reaction method or the logarithmic direct method (consult [Pahle2009] for a review). Based on the first reaction method is a prominent algorithm to simulate spatially inhomogeneous reaction-diffusion networks, the next-subvolume method [Elf2004]. The popular software packages Smartcell and MesoRD can handle the next-reaction and the next-subvolume methods. The fastest implementation of the next-subvolume method so far is the stochastic simulation compiler [Lis2009].

All algorithms in the previous paragraph compute exact realizations of stochastic reaction-diffusion systems. The disadvantage of these methods is their high computational cost, in particular, if a fine granularity is required and the number of subvolumes is high. Furthermore, they do not lend themselves well for data-parallel implementations. However, if one is willing to sacrifice accuracy for speed, deterministic-stochastic hybrid algorithms provide an efficient alternative. In these methods, the diffusion part is separated from the reaction part and treated deterministically. The Gillespie multiparticle method (GMP) [Rodriguez2006] is one example of this class of algorithms.

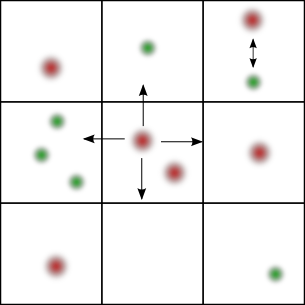

GMP handles the diffusion part of the reaction-diffusion network trough a multiparticle lattice gas automaton and the reaction part via Gillespie’s direct method. The time step is chosen globally according to the diffusion constants of each species and the dimensions of each lattice cell. In each iteration, all reactions are performed independently in each subvolume. At the end of the time step all particles are diffused according to the cellular automaton rule. Accomodating spatially inhomogeneous systems with a drift field is substantially harder [Vigelius2012a]. In particular, the time step needs to be computed for each cell separately and the global time step is minimized over the domain. The transition probabilities in each cell then need to be scaled to the new time step. Details about how this can be achieved are found in [Vigelius2012a].

GPU Implementation¶

With the advent of general-purpose graphics processing units there is potential to provide super-computing resources to a broad audience. GPUs are ubiquitous and comparably cheap and designated units can be mounted in work station computers for better performance. GPUs provide a multitude of processing threads which are executed in parallel. We devised a data-parallel implementation of GMP on GPUs, allowing researchers to efficiently simulate spatially-inhomogeneous reaction-diffusion networks. The latest extensions support fully non-linear, inhomogeneous, reaction-drift-diffusion simulations. Even on common work stations, it can still provide speed gains of one to two orders of magnitude. The particular strength of the GPU-accelerated approach unfolds when a GPU cluster is used. In this case, a second level of parallelization over experiments is possible which result in another several orders of magnitued performance gain. This two-level parallelization enables complex experiments, such as parameter sweeps or even parameter optimization, and thus unlocks entirely new application areas.

Basic Workflow¶

The Inchman package consists of the web-based Editor and the command-line client. The editor creates an SBML file which is amended with Inchman-specific information, in particular the spatial setup and the simulation paramters. The command-line client works on these files and creates an HDF5 file. HDF5 files are supported by most major software packages, in particular, Python, Matlab and Mathematica.

The general workflow, which would be sufficient for most applications, is as follows:

- Create your reaction-drift-diffusion network using the Editor.

- Save it to an SBML file or directly send it to the Inchman client.

- Simulate the model on your computer (or on any GPU-enabled machine).

- Retrieve the output HDF5 file and analyze it (using Python, Matlab, Mathematica..)

Alternatively, you could do any of the following (from simple to very advanced):

- Use your favourite SBML editor (e.g. CellDesigner) to create a non-spatial SBML file and amend it with Inchman

- Write up the spatial SBML files yourself (not recommended) or use a script to generate them

- The core simulation module is a shared library so you can link your own code to this library, use the Inchman C++ API to build the model and simulate it.

References¶

| [Elf2004] | Elf J., Ehrenberg, M. (2004): Spontaneous separation of bi-stable biochemical systems into spatial domains of opposite phases Systems Biology, IEE Proceedings , vol.1, no.2, pp.230,236, 1 Dec. 2004 doi: 10.1049/sb:20045021 |

| [Gillespie2007] | Gillespie D T (2007): Stochastic Simulation of Chemical Kinetics Annual Review of Physical Chemistry 58: 35-55 |

| [Lis2009] | Lis M, Artyomov M N, Devadas S, Chakraborty A. K. (2009). Efficient stochastic simulation of reaction-diffusion processes via direct compilation. Bioinformatics, 25(17), 2289–2291. |

| [Pahle2009] | Pahle J (2009): Biochemical simulations: stochastic, approximate stochastic and hybrid approaches Brief Bioinform. 10(1): 53–64. |

| [Rodriguez2006] | Rodriguez J V, Kaandorp J A, Dobrzyski M, Blom J G (2006). Spatial stochastic modelling of the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase (pts) pathway in escherichia coli. Bioinformatics, 22(15), 1895–1901. |

| [Vigelius2010] | Vigelius M, Lane A, Meyer B (2010): Accelerating reaction–diffusion simulations with general-purpose graphics processing units Bioinformatics (2011) 27 (2): 288-290. |

| [Vigelius2012a] | (1, 2, 3) Vigelius M, Meyer B (2012a) Multi-Dimensional, Mesoscopic Monte Carlo Simulations of Inhomogeneous Reaction-Drift-Diffusion Systems on Graphics-Processing Units. PLoS ONE 7(4): e33384. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033384 |

| [Vigelius2012b] | Vigelius M, Meyer B (2012b): Stochastic Simulations of Pattern Formation in Excitable Media. PLoS ONE 7(8): e42508. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042508 |