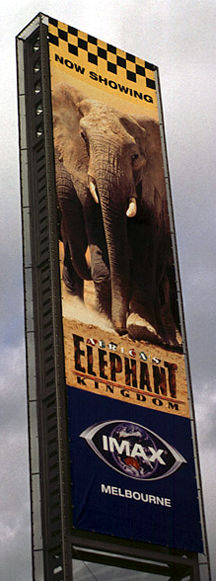

| ...you have the world's biggest screen. Here we see some banners outside Melbourne's recently opened IMAX cinema, part of the Melbourne museum. | ||

|

In Burke's account of the sublime, a key element that differentiated the sublime from the merely familiar, comprehensible, and reassuring picturesque, was the notion of terror. This terror is a mediated or bounded terror, one that allows the viewer to be placed at the boundary of danger, yet preserving a certain distance from it. |

|

|

Much of the sublime is about measuring ourselves against the overwhelming scale of a boundless nature. This is not only enforced by visual culture, but by almost all technology. If one of IMAX's goals is to free the frame — to become boundless — then it comes as little surprise that much of the subject matter shown at IMAX is about nature and natural history. It is also no coincidence that many IMAX cinemas around the world are located in close proximity to museums (particularly science and natural history museums) or great "natural wonders". Museums present a world-view favouring the authority of science, both directly in the form of the power of the scientific method, and implicitly as a sense of morality about our relationship with the other species of plants and animals with whom we share the earth. As a cinematographic medium, IMAX is still in its infancy, but in terms of its cultural pose, it is highly developed. Most IMAX programs are nature documentaries which, like the classical museum, take us to a mythical exotica located within a wild, distant place — a distance far from where you are, made uncomfortably close by technology. But the emphasis on 'uncomfortably close' should be expanded — it isn't really that uncomfortable, it attempts the 'pleasurable terror' of the sublime. Does it succeed? The problem is that there is no wild any more. The notion of the untamed wilderness is a romantic, Rousseau-esque fantasy. Consider, even, the task of getting to the wild and exotic places that are depicted in the IMAX films. Distance is again telescoped by technology: travel brochures, strategically located at the IMAX cinema exit, offer daily flights to African safari parks. No matter where you go on earth you can hear the distant sound of jet engines as flight paths cris-cross the translucent atmosphere of a bounded planet, spewing toxins into ruined air at unnerving speed. The images of animals on the IMAX screen are desperately trying to free themselves from the frame of the screen. IMAX is a vast technological magic act that attempts to fool the viewer into the belief that the screen has no bounds, that the bounded artificial has, at last, been set free to become the unbounded natural. As the narrator's voice booms before the show: “IMAX! Bigger than you can imagine.” IMAX does hold terror, but it is a pleasurable terror, of a mere 45 minutes duration, that dissipates and vanishes shortly after you have left the comfort of your seat. There is no real terror or danger here, no real wild. The stories, under the guise of documentary, are contrived as anthropomorphic narrative that has well passed its use-by date. That 'endangered species' have given way to 'biodiversity', is still an area that most IMAX films have yet to come to grips with. Biodiversity denies heroes, but endangered species create them. |

||